“Hi Naz, my name is Shaza. You changed my life. Can I buy you coffee?”

I sent this cold DM to Naz Hamid in March 2020 while stranded in San Francisco when COVID cancelled the conference that brought me there. After fifteen years of following him on Twitter and consuming his thoughtful writing about craft and community, I finally worked up the courage to message him.

Back in 2008, I was a Malaysian designer working across cultures and continents, riding the Web 2.0 wave, trying to figure out technology and nurture this seed of a studio called Stampede.

Discovering Naz, a fellow Malaysian designer navigating Silicon Valley, made me feel seen. Someone who understood that craft is its own reward. That seeking meaning in our work isn’t unusual.

Someone from here, who looked like me and was obsessed over things that seemed small to others but mattered deeply to us.

I later learned this was the power of representation. Being in similar places now, it’s a responsibility I don’t take lightly.

What started as dinner…

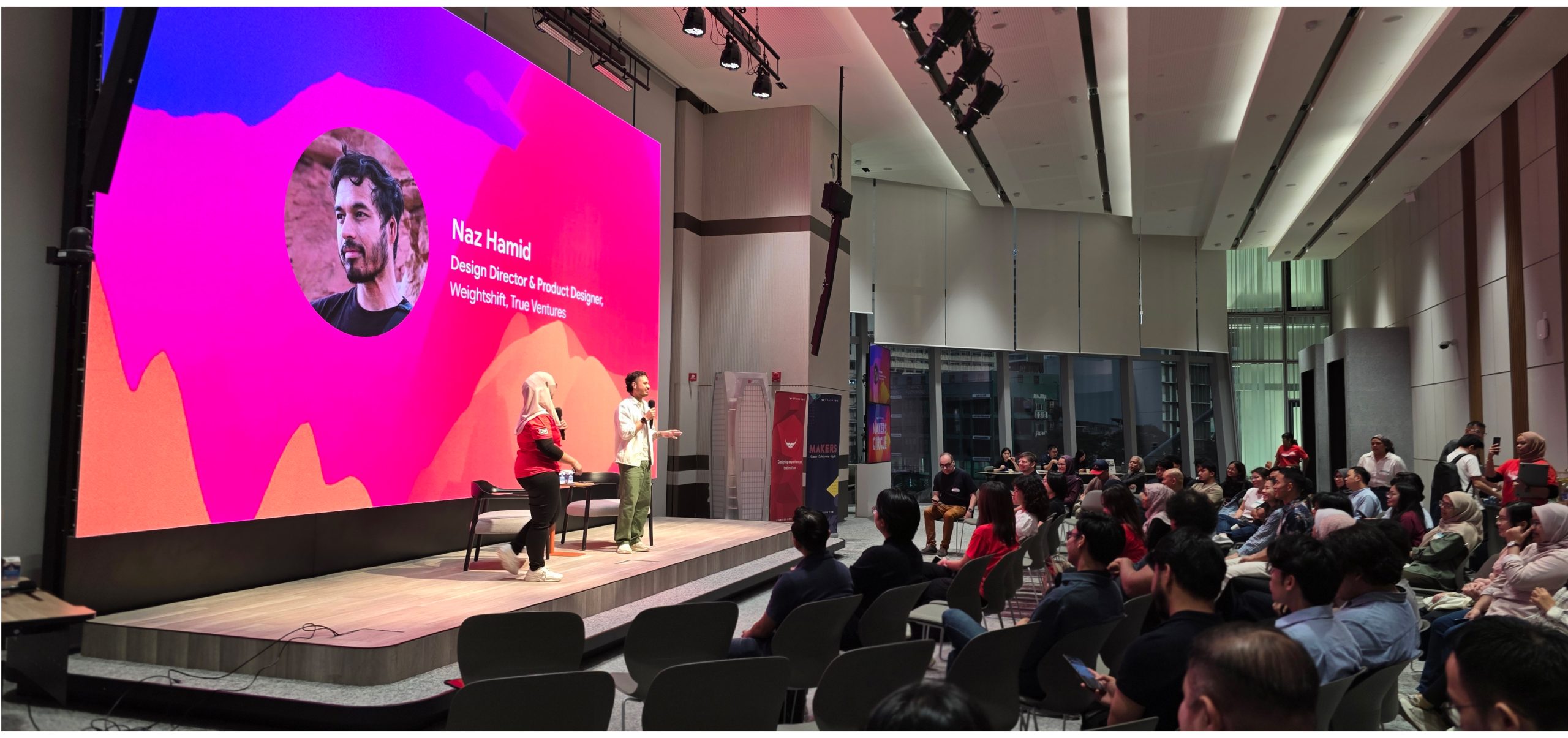

Like the best of things, none of this was planned. Two weeks before his visit, Naz got in touch so we could meet in KL. What started as dinner plans turned into a homecoming, a return to Malaysia and also to a community of practitioners who share his curiosity about craft and meaning.

“Back in 2000, there were maybe a handful of web designers in the world,” Naz reflected, talking about the early days when people built the internet because they were curious, not because there was money in it. “And then more recently, at Config, I saw thousands of designers at Moscone Centre and thought, wow, look how far our profession has come.”

Our Makers Circle format is borrowed from those old Parisian salons where intellectuals gathered and talked to each other late into the evening. There, there was intentionality, a choice for quiet conversation and a space created for thinking together.

UOB’s beautiful hall was perfect for this kind of discourse. It was spacious for deep conversations and elegant to honour the discourse. Our thanks to them for hosting us again.

Starting with intention

But the evening started with something you’d never see at a tech conference: silence.

Naz guided seventy practitioners through a brief meditation, asking us to let go of whatever had been eating at us all day. The whole hall was quiet, lights dimmed, eyes closed. We let go of the day’s scattered energy and entered the Circle with open hearts and minds.

I loved the renewed evening energy.

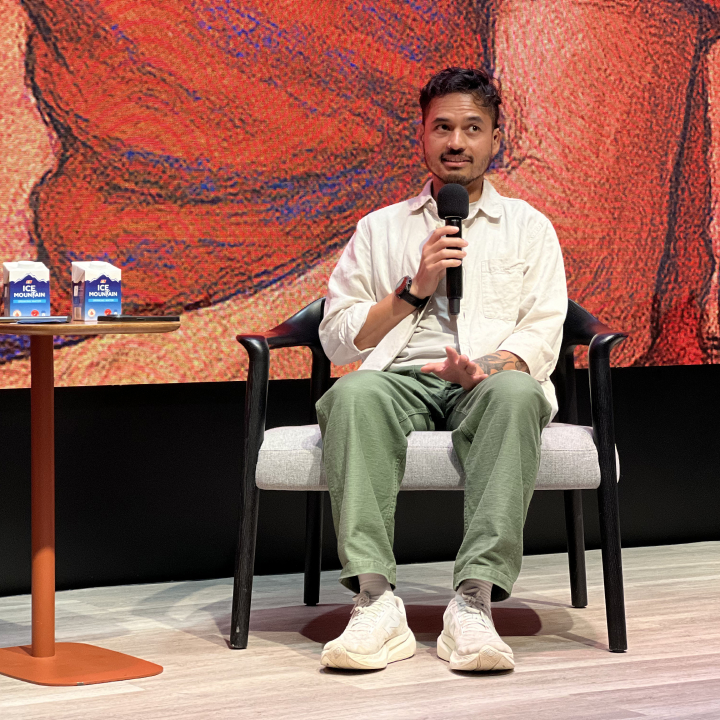

Naz’s Perspectives: philosophy, meets practice

Now whenever Naz and I talk, it somehow always comes back to craft. He’s the kind of friend you can pick up conversations with months later, exactly where you left off.

In fact, I learned the word “shokunin” from Naz. It’s this Japanese idea of master craftspeople who spend their entire lives perfecting one thing. Not just skill, but people who dedicate themselves completely to their craft, finding deep purpose in perfecting the smallest details.

Watching Naz share his Silicon Valley experience made it feel like thoughts and ideas were clicking into place. He talked about experiencing multiple booms and busts, his work at True Ventures and designing for inclusion. He shared how his team’s redesign of Adobe.com failed with Japanese audiences because it lacked that consideration for cultural diversity and understanding the culture and environment in which the design lives and breathes.

In the midst of figuring out what it actually means to make things when machines are getting better at making them too, these are the stories that stick with you. There’s tendency to gravitate towards success stories but mind the survivorship bias. Most times, it’s real failures that teach you something.

AI and the future of craft

We also touched on AI replacing designers. Naz shared a beautiful story about Bruce Swedien, the legendary sound engineer who worked with Michael Jackson.

Bruce was never afraid to share his knowledge. He taught workshops, wrote books and discussed his experiences openly. He’d share how he and MJ would tinker with mixes for hours, making over 90 different versions of “Billie Jean” alone.

When people asked if he was concerned others would copy the techniques he so generously shared, Bruce’s response was profound: nobody could replicate his creative future, just his past techniques.

Post-Circle, that was the bit that got me thinking. I was curious, so I Googled bruce up. Which led me to something he said that really resonates with designers navigating automation today.

Back in 2006, when digital sales were overtaking CDs, inexpensive hardware and software meant musicians could craft professional-level recordings from their bedrooms. Bruce saw this shift but far from being defensive, he was jubilant.

“What I find most promising now is that musicians have easy access to recording technology that is far better than at any time in the past. The music recording is going to be put back in the hands of people who truly love music for music’s sake.”

Replace “recording technology” with “AI tools” and his vision becomes rather prescient.

The shift to meaning

“There’s this rejection happening,” Naz said of senior designers globally who are walking away from big corporate jobs to do work that actually matters. “After Jason Santa Maria left Shopify and Ethan Marcotte left 18F, everyone’s doing their own thing again. We all want to do things that matter and practice our craft.”

The value hierarchy is shifting.

These are experienced practitioners who’ve seen how corporate pressures can dilute good work. They’re not rejecting profit. They’re rejecting the specific trade-offs that come with a scale-at-all-costs culture.

It reminds me of how my friend Ben Bowes at GovTech Singapore puts it perfectly: “Earlier in my career, I spent a lot of time in what I call the ‘more industry.’ Helping companies get people to buy more, watch more, consume more. After a while, it wore me down. I wanted my work to mean more than an uptick in shareholder value.”

This wasn’t some abstract philosophy. It lives in the choices we make.

The Salon Experiment: flipping the script

Naz and I then experimented with something we don’t often see at a tech event: a proper salon. Borrowing from those 18th-century Parisian gatherings where intellectuals debated ideas long into the evening, we turned the audience from passive listeners into the real stars of the show.

Naz moved around the audience, no longer the visiting expert but genuinely curious about what we’re building here. The role reversal was beautiful. He asked the questions and people responded with shared insights about Malaysian design that Silicon Valley rarely gets to hear.

“How many of you know each other here?” Quite a few hands went up—many had attended our larger Makers gatherings. But among them I spotted a good few newcomers too, joining our tight-knit community for the first time.

“What’s the actual state of things here? The real practitioner version?”

What happened next felt like watching trust build in real time. People opened up.

They shared design journeys, accomplishments, frustrations and the emergence of distinctly Malaysian design language thanks to #sapotlokal campaigns post-COVID.

We talked about layoffs and uncertainty, navigating pivots to entrepreneurship, ideas worth building and who to build them with.

So what did we figure out about being Malaysian

One trait many Malaysians share is humble underdoggedness. Humility is a virtue here, but it also creates a massive blind spot. We couldn’t see far into what makes us great and so it was doubly beautiful watching the non-Malaysians in the room remind us of our strengths.

“As an outsider working with Malaysians, I value your cultural insight,” someone said. “Malaysians are fantastic multicultural bridges. What you do so naturally—navigating between cultures with fluency and warmth—is truly a superpower.”

“Malaysians can code-switch effortlessly,” someone else said. “Put us anywhere, and we figure our way out.”

Naz, coming from his Silicon Valley perspective, backed this up: “Living between worlds develops empathy across cultures. That naturally leads to more inclusive design.”

The consensus is we’re not trying to be Western designers who happen to be Malaysian. We’re Malaysian designers whose cultural fluency creates value that others can’t replicate. We don’t have to choose between local and global. Our between-worlds position makes us perfect for this role.

Vulnerability and courage

Did our experiment work? Many times over. The salon format gave people permission to be vulnerable alongside being knowledgeable. Senior practitioners admitted knowledge gaps. Founders talked about fear. Designers share the dilemma of using AI to deepen their craft while risking being made obsolete by it.

“I think I’m missing foundational design knowledge and I want to do something about it,” one designer admitted, with the rest of the room nodding along.

I found this moment particularly moving because it takes courage to admit gaps when everyone expects you to have it all figured out. This was the great collective figuring-out. I enjoyed every bit of it.

How we think about technology and taste

One exchange that stays with me is how we talked about technology and taste. It felt refreshingly grounded instead of panicked or blindly optimistic. There’s a real desire for thoughtful integration here.

The unfortunate reality is that commercialism rewards speed above all else. Designers get praised for assembling interfaces quickly, for churning out converting designs fast. But this creates a trap. When automation arrives, the assemblers are the first to go. Along the way, taste gets lost.

If we look around us, the pattern is glaringly obvious. Websites look the same. Platforms sound the same. Design has become homogenous. Faster, yes. Better? Not always.

We’ve become dependent on pre-built components, reinforcing our role as assemblers rather than creators. We’ve optimised for efficiency at the cost of the very thing that makes our work human—distinctiveness and meaning.

Backstage, Naz talked about inspiration. Not those from Dribbble or Mobbin, where we recycle the same patterns endlessly. But from architecture, from nature, from other mediums and cultural traditions. Originality lives in the spaces between disciplines, where we still get to lean on our curiosity and algorithms haven’t yet flattened everything into sameness.

The irony is that designers who create from first principles often deliver better results faster. Not because they work slowly but because they tap into what makes people feel cared for. When something resonates deeply with users, it succeeds more quickly in the market.

This reminds me of how Sir Jony Ive put it beautifully in his Stripe talk:

“I really do believe that we have this ability to sense care. It’s easy in a service because you confront care, because you confront the person. When it’s vicarious, when it’s via an object, when it’s via a piece of software, it’s more complex. But I think you can sense carelessness. You know carelessness. And so, I think it’s reasonable to believe that you also know care, and you sense care.”

This explains why homogenous design feels hollow. It lacks human intention. When everything looks the same, it’s often because it was optimised for production speed rather than crafted with the person in mind. The result is faster assembly but lower differentiation and substance.

Speed of assembly isn’t the same as speed of success.

The family dimension

Perhaps the most moving moment came when Naz’s 75-year-old mother joined us. Like many Asian parents, she’s never quite understood what her son does with “these Internet things.” Neither does mine!

In Asian families, elders are woven into the fabric of our achievements. But in technology, our accomplishments often exist in languages our elders don’t speak. Watching Naz’s mother see her son command respectful attention from a room full of professionals transformed the evening from a professional gathering into a cultural homecoming.

Between Worlds: where we go from here

Like those early web designers Naz remembers, we’re approaching technology with curiosity rather than fear. We’re building for global markets but celebrating local culture.

Innovation’s future won’t be determined solely in Silicon Valley. It’s being shaped by practitioners who understand that meaningful progress happens between worlds—where Eastern wisdom guides Western technology, where community discourse creates competitive advantage.

This is our distinctive contribution: not choosing between tradition and innovation, but finding harmony between both.

For me, hosting is always a treat in itself. You plan the structure and then let the gathering take its own flow.

By evening’s end, something had shifted. We ran over by 30 minutes, yet nobody looked at their phone except for photos. This felt different.

As I watched Naz’s mother beam with pride, I dare say we’d created something unprecedented: a gathering that honours both individual craft excellence and collective cultural wisdom.

My team and I at Stampede feel deeply grateful we get to create this space for discourse. One Makers at a time, we’re building community that chooses craft over convenience, meaning over metrics, depth over noise.

The future belongs to those who remember that design is both craft and responsibility. We’re just getting started.

—

Next up: The conversation about craft and taste in the age of AI continues at Makers 12 on 27th September. Registration opens soon.

Special thanks to Naz Hamid, UOB Malaysia, my wonderful team at Stampede and every practitioner who made this gathering possible. – Shaza